Branching and Merging

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I or my team work on multiple features in parallel?

How can changes from parallel tracks of work be combined?

Objectives

Explain what git branches are and when they should be used

Use a branch to develop a new feature and incorporate it into your code

Identify the branches in a project and which branch is currently in use

Describe a scalable workflow for development with git

Motivation for branches

In the previous section we tracked a guacamole recipe with Git.

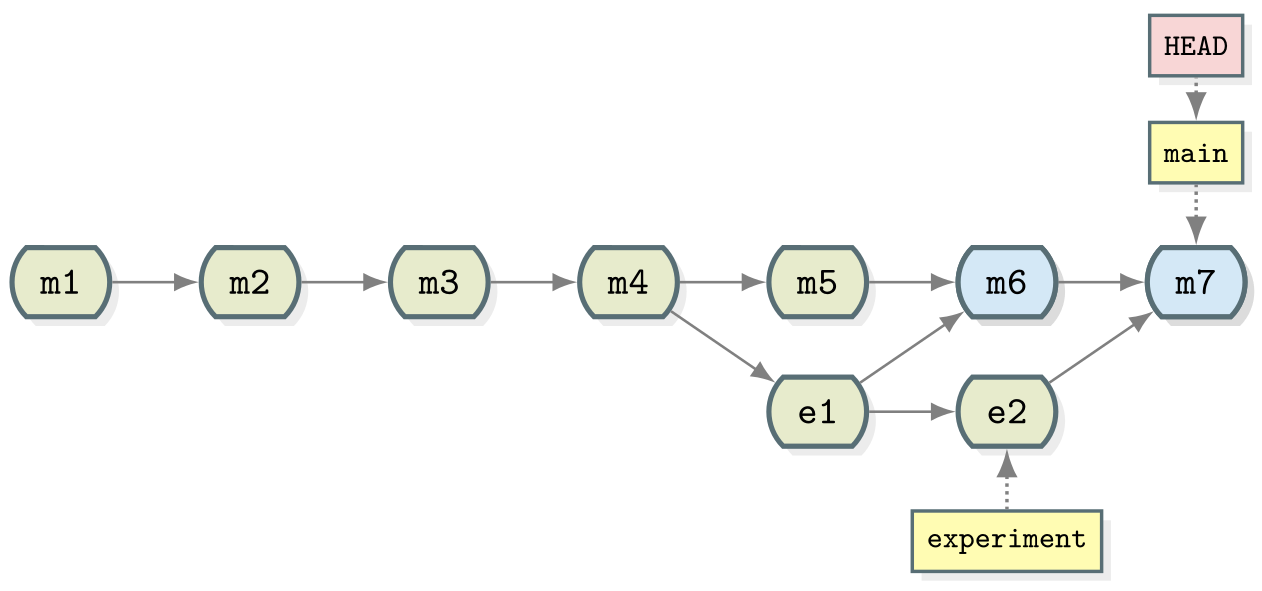

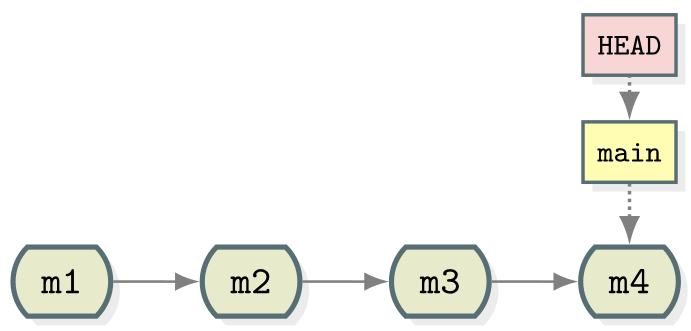

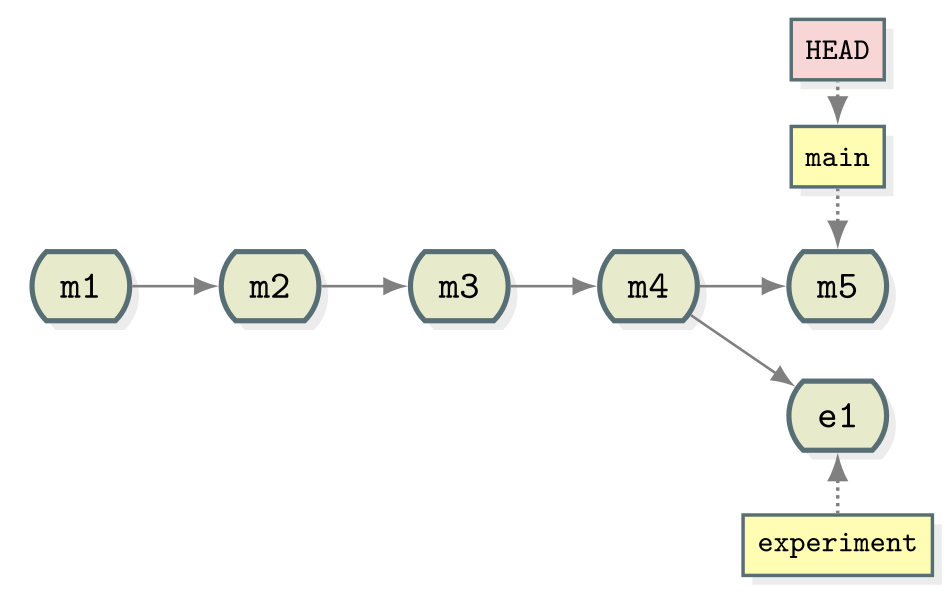

Up until now our repository had only one branch with one commit coming after the other:

- Commits are depicted here as little boxes with abbreviated hashes.

- Here the branch

mainpoints to a commit. - “HEAD” is the current position (remember the recording head of tape recorders?).

- When we talk about branches, we often mean all parent commits, not only the commit pointed to.

Now we want to do this:

Software development is often not linear:

- We typically need at least one version of the code to “work” (to compile, to give expected results, …).

- At the same time we work on new features, often several features concurrently. Often they are unfinished.

- We need to be able to separate different lines of work really well.

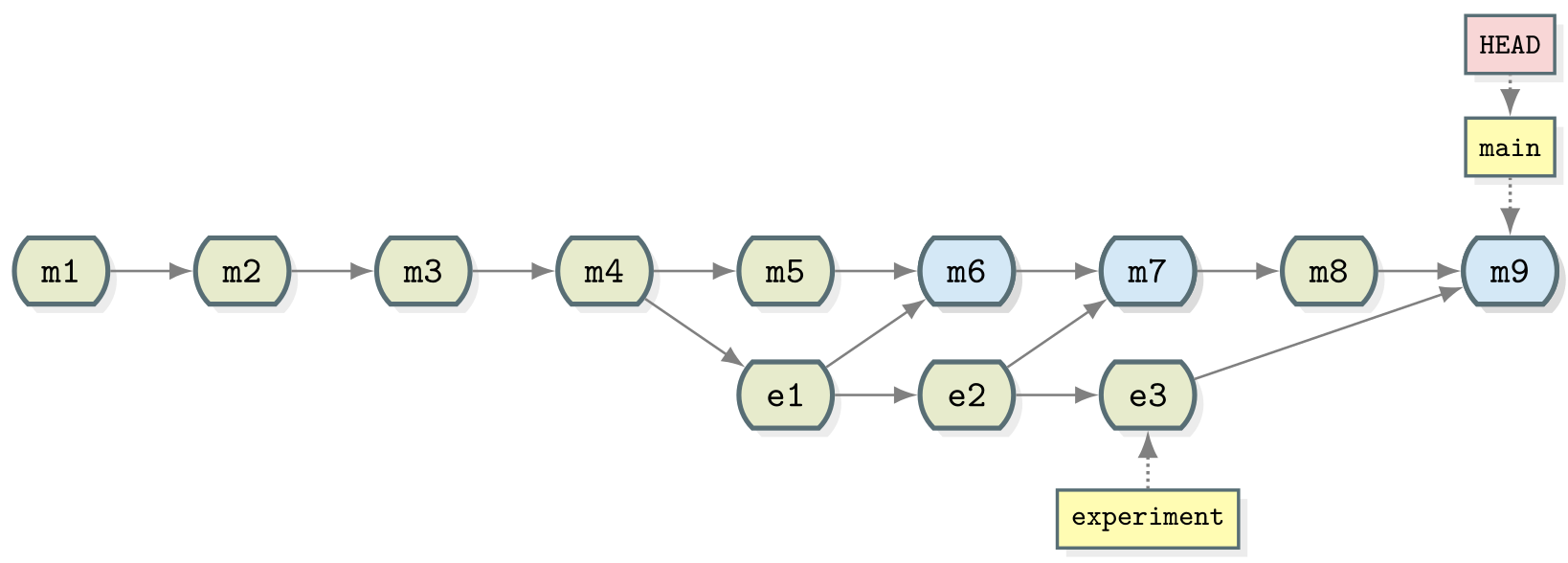

The strength of version control is that it permits the researcher to isolate different tracks of work, which can later be merged to create a composite version that contains all changes:

- We see branching points and merging points.

- Main line development is often called

main. - Other than this convention there is nothing special about

main, it is just a branch. - Commits form a directed acyclic graph (arrows point from parent commits to child commits).

- Commits are relative to the preceding (parent) commit. Whilst we

previously talked about Git taking “snapshots” of your project this is

slightly misleading. Git actually records the changes made since the last

commit. The difference is subtle but powerful, it makes commands like

git revertpossible.

A group of commits that create a single narrative are called a branch. There are different branching strategies, but it is useful to think that a branch tells the story of a feature, e.g. “fast sequence extraction” or “Python interface” or “fixing bug in matrix inversion algorithm”.

Which Branch Are We Using?

To see where we are (where HEAD points to) use git branch:

$ git branch

* main

- This command shows where we are, it does not create a branch.

- There is only

mainand we are onmain(star represents theHEAD).

In the following we will learn how to create branches, how to switch between them and how to merge changes from different branches.

A useful alias

We will now define an alias in Git, to be able to nicely visualize branch structure in the terminal without having to remember a long Git command (more details about what aliases are can be found here and the full docs on how to set them up in Git are here):

$ git config --global alias.graph "log --all --graph --decorate --oneline"

Creating and Working with Branches

Firstly lets take stock of the current state of our repository:

$ git graph

* ddef60e (HEAD -> main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

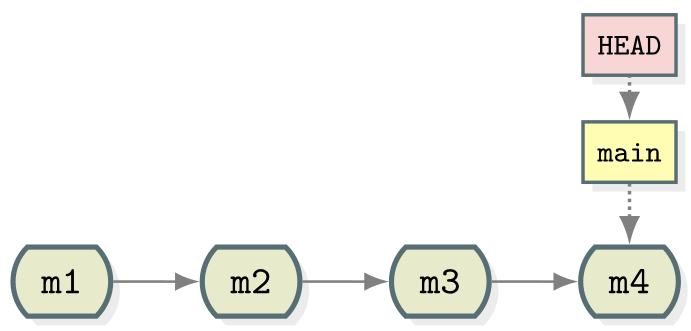

We have four commits and you can see that we are working on the main branch

from HEAD -> main next to the most recent commit. This can be represented

diagrammatically:

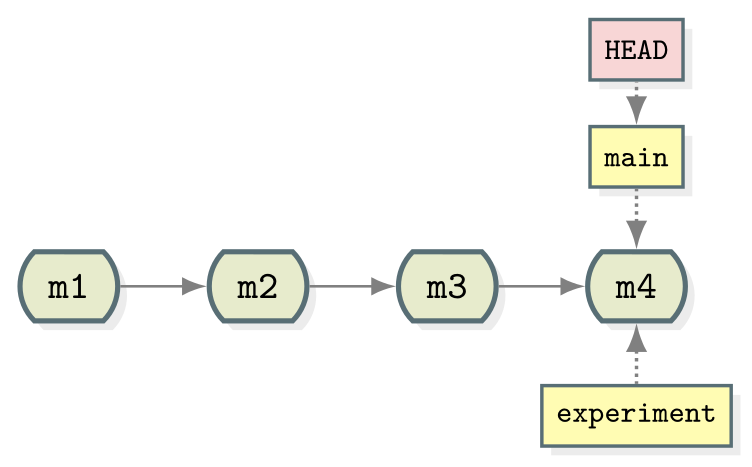

Let’s create a branch called experiment where we try out adding some

coriander to ingredients.md.

$ git branch experiment

$ git graph

* ddef60e (HEAD -> main, experiment) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

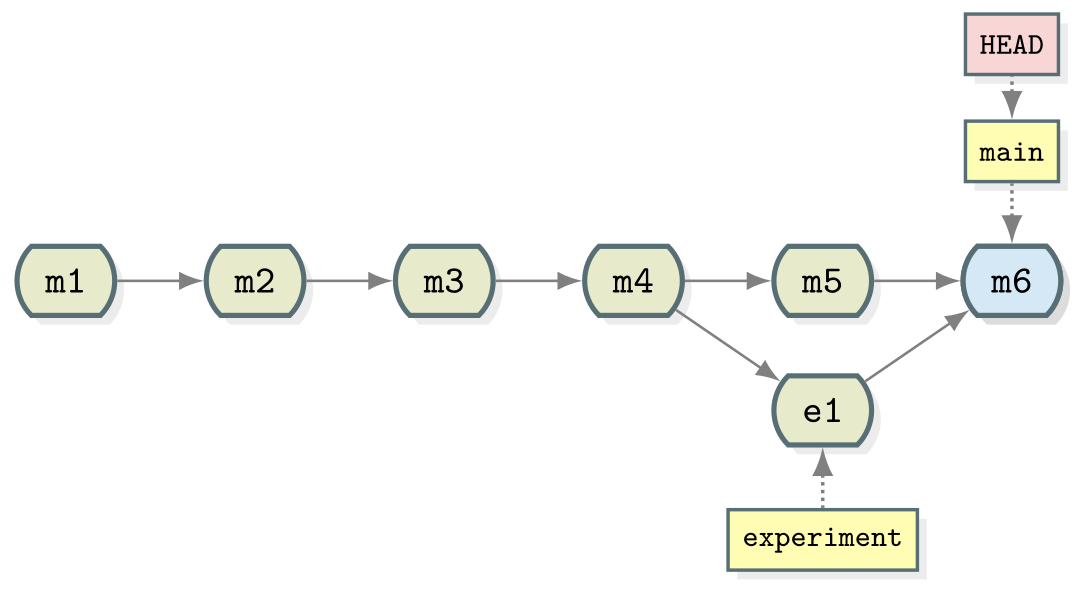

Notice that the name of our new branch has appeared next to latest commit. HEAD is still pointing main however denoting that we have created a new branch but we’re not using it yet. This looks like:

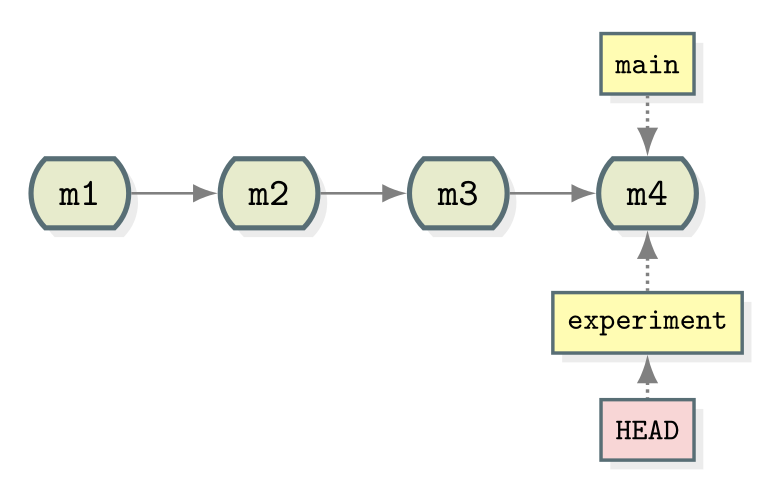

To start using the new branch we need to check it out:

$ git checkout experiment

$ git graph

* ddef60e (HEAD -> experiment, main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

Now we see HEAD -> experiment next to the top commit indicating that we are

now working with, and any commits we make will be part of the experiment

branch. As shown before which branch is currently checkout out can be confirmed

with git branch.

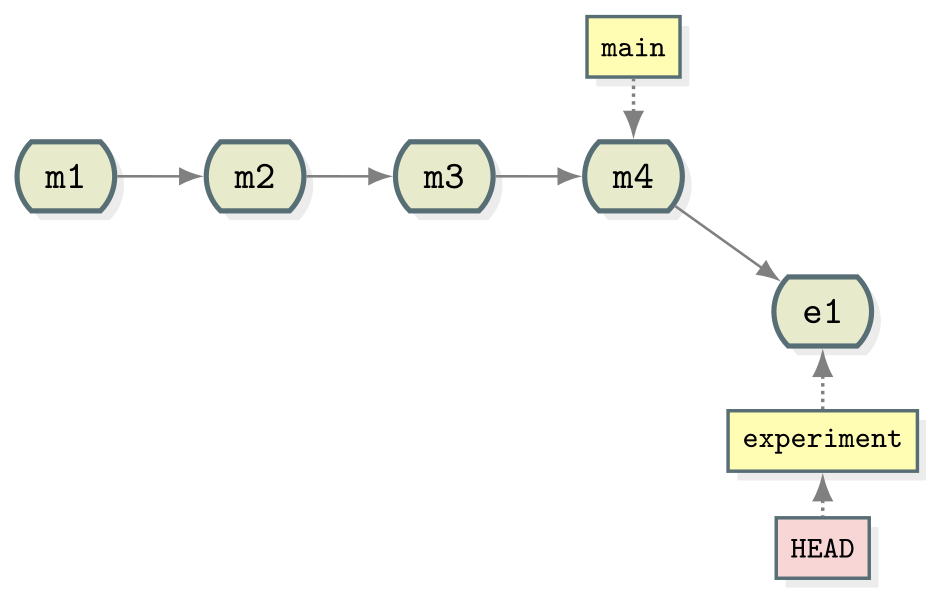

Now when we make new commits they will be part of the experiment branch. To

test this let’s add 2 tbsp coriander to ingredients.md. Stage this and commit

it with the message “try with some coriander”.

$ git add ingredients.md

$ git commit -m "try with some coriander"

$ git graph

* 96fe069 (HEAD -> experiment) try with some coriander

* ddef60e (main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

Note that the main branch is unchanged whilst a new commit (labelled e1) has

been created as part of the experiment branch.

As mentioned previously, one of the advantages of using branches is working on

different features in parallel. You may have already spotted the typo in

ingredients.md but let’s say that we’ve only just seen it in the midst of

our work on the experiment branch. We could correct the typo with a new commit

in experiment but it doesn’t fit in very well here - if we decide to discard

our experiment then we also lose the correction. Instead it makes much more

sense to create a correcting commit in main. First, move to (checkout) the master branch:

$ git checkout main

Then fix the typing mistake in ingredients.md. And finally, commit that change:

$ git add ingredients.md

$ git commit -m "Corrected typo in ingredients.md"

$ git graph

* d4ca89f (HEAD -> main) Corrected typo in ingredients.md

| * 96fe069 (experiment) try with some coriander

|/

* ddef60e Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

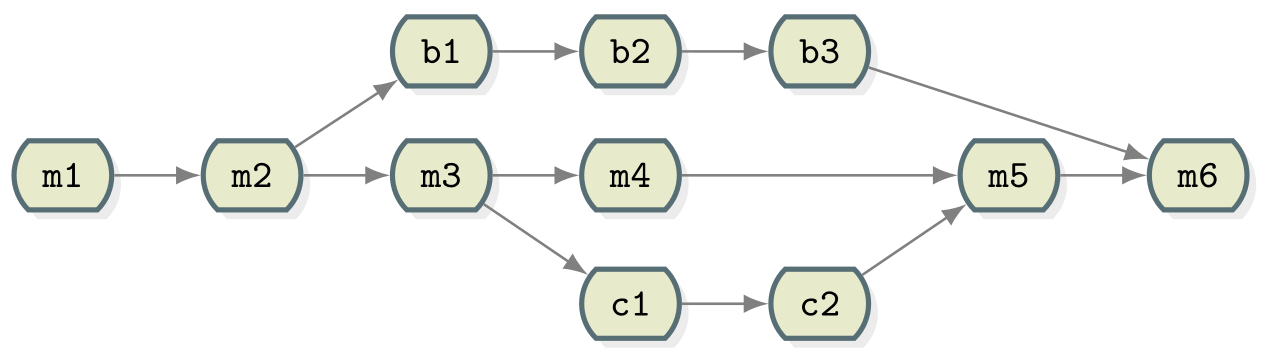

Merging

Now that we have our two separate tracks of work they need to be combined back

together. We should already have the main branch checked out (double check

with git branch). The below command can then be used to perform the merge.

$ git merge --no-edit experiment

Merge made by the 'ort' strategy.

ingredients.md | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

now use:

$ git graph

* 40070a5 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 96fe069 (experiment) try with some coriander

* | d4ca89f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* ddef60e Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

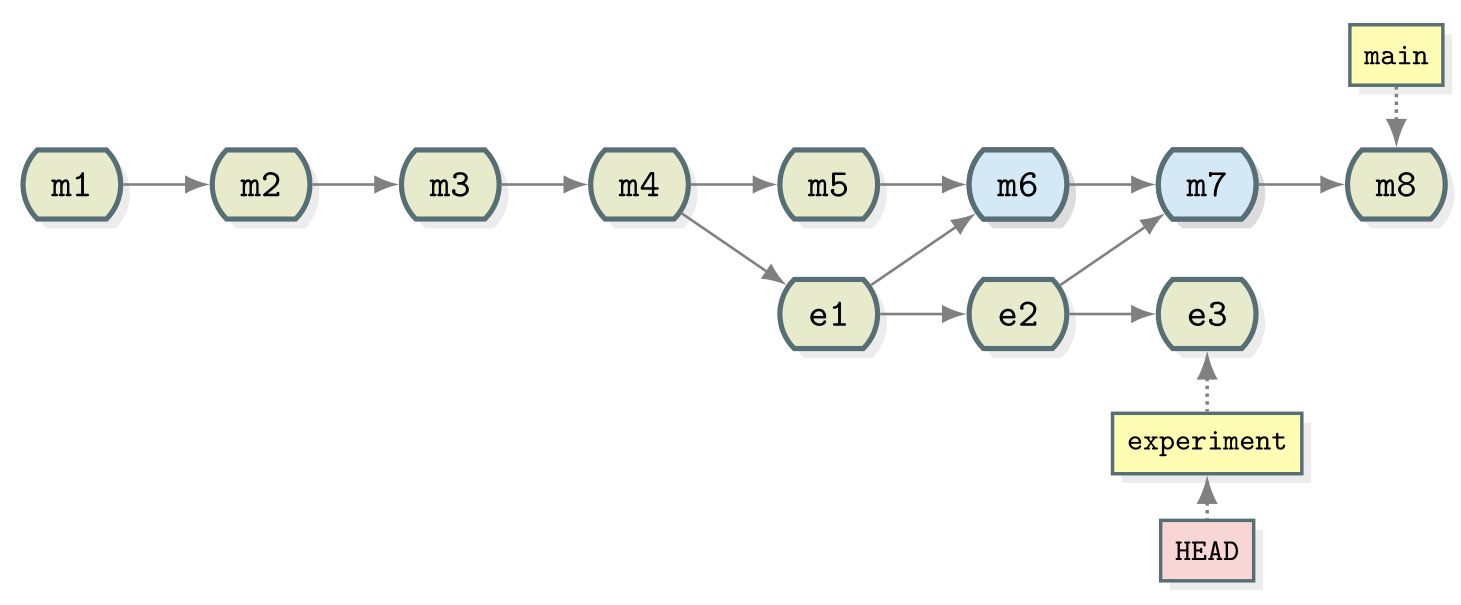

Merging creates a new commit in whichever branch is being merged into that contains the combined changes from both branches. The commit has been highlighted in a separate colour above but it is the same as every commit we’ve seen so far except that it has two parent commits. Git is pretty clever at combining the changes automatically, combining the two edits made to the same file for instance. Note that the experiment branch is still present in the repository.

Now you try

As the experiment branch is still present there is no reason further commits can’t be added to it. Create a new commit in the

experimentbranch adjusting the amount of coriander in the recipe. Then mergeexperimentintomain. You should end up with a repository history matching:Solution

$ git checkout experiment $ # make changes to ingredients.md $ git add ingredients.md $ git commit -m "Reduced the amount of coriander" $ git checkout main $ git merge --no-edit experiment $ git graph* 567307e (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'experiment' |\ | * 9a4b298 (experiment) Reduced the amount of coriander * | 40070a5 Merge branch 'experiment' |\ \ | |/ | * 96fe069 try with some coriander * | d4ca89f Corrected typo in ingredients.md |/ * ddef60e Revert "Added instruction to enjoy" * 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients * 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy * ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

Conflicts

Whilst Git is good at automatic merges it is inevitable that situations arise where incompatible sets of changes need to be combined. In this case it is up to you to decide what should be kept and what should be discarded. First lets set up a conflict:

$ git checkout main

$ # change line to 1 tsp salt in ingredients.md

$ git add ingredients.md

$ git commit -m "Reduce salt"

$ git checkout experiment

$ # change line to 3 tsp in ingredients.md

$ git add ingredients.md

$ git commit -m "Added salt to balance coriander"

$ git graph

* d5fb141 (HEAD -> experiment) Added salt to balance coriander

| * 7477632 (main) reduce salt

| * 567307e Merge branch 'experiment'

| |\

| |/

|/|

* | 9a4b298 Reduced the amount of coriander

| * 40070a5 Merge branch 'experiment'

| |\

| |/

|/|

* | 96fe069 try with some coriander

| * d4ca89f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* ddef60e Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

Now we try and merge experiment into main:

$ git checkout main

$ git merge --no-edit experiment

Auto-merging ingredients.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in ingredients.md

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

As suspected we are warned that the merge failed. This puts Git into a special

state in which the merge is in progress but has not been finalised by creating a

new commit in main. Fortunately git status is quite useful here:

$ git status

On branch main

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

(use "git merge --abort" to abort the merge)

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: ingredients.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

This suggests how we can get out of this state. If we want to give up on this

merge and try it again later then we can use git merge --abort.. This will

return the repository to its pre-merge state. We will likely have to deal with

the conflict at some point though so may as well do it now. Fortunately we don’t

need any new commands. We just need to edit the conflicted file into the state

we would like to keep, then add and commit as usual.

Let’s look at ingredients.md to understand the conflict:

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

<<<<<< HEAD

* 1 tsp salt

=======

* 3 tsp salt

>>>>>> experiment

* 1/2 onion

* 1 tbsp coriander

Git has changed this file for us and added some lines which highlight the

location of the conflict. This may be confusing at first glance (a good editor

may add some highlighting which can help), but you are essentially being asked

to choose between the two versions presented. The tags <<<<<<< HEAD and

>>>>>>> experiment are used to indicate which branch each version came from

(HEAD here corresponds to main as that is our checked out branch).

The conflict makes sense, we can either have 1 tsp of salt or 3. There is no way

for Git to know which it should be so it has to ask you. Let’s resolve it by

choosing the version from the main branch. Edit ingredients.md so it looks

like:

* 2 avocados

* 1 lime

* 1 tsp salt

* 1/2 onion

* 1 tbsp coriander

now stage, commit and check the result:

$ git add ingredients.md

$ git commit -m "Merged experiment into main"

$ git graph

* e361d2b (HEAD -> main) Merged experiment into main

|\

| * d5fb141 (experiment) Added salt to balance coriander

* | 7477632 reduce salt

* | 567307e Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| |/

| * 9a4b298 Reduced the amount of coriander

* | 40070a5 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\ \

| |/

| * 96fe069 try with some coriander

* | d4ca89f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* ddef60e Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 8bfd0ff Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

* 2bf7ece Added instruction to enjoy

* ae3255a Adding ingredients and instructions

Summary

Let us pause for a moment and recapitulate what we have just learned:

$ git branch # see where we are

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git checkout <name> # switch to branch <name>

$ git merge <name> # merge branch <name> (to current branch)

Since the following command combo is so frequent:

$ git branch <name> # create branch <name>

$ git checkout <name> # switch to branch <name>

There is a shortcut for it:

$ git checkout -b <name> # create branch <name> and switch to it

Typical workflow

These commands can be used in a typical workflow that looks like the below:

$ git checkout -b new-feature # create branch, switch to it

$ git commit # work, work, work, ...

# test

# feature is ready

$ git checkout main # switch to main

$ git merge new-feature # merge work to main

$ git branch -d new-feature # remove branch

Key Points

Git allows non-linear commit histories called branches

A branch can be thought of as a label that applies to set of commits

Branches can and should be used to carry out development of new features

Branches in a project can be listed with git branch and created with git branch branch_name

The HEAD refers to the current position of the project in its commit history

The current branch can be changed using git checkout branch_name

Once a branch is complete the changes made can be integrated into the project using git merge branch_name

Merging creates a new commit in the target branch incorporating all of the changes made in a branch

Conflicts arise when two branches contain incompatible sets of changes and must be resolved before a merge can complete

Identify the details of merge conflicts using git diff and/or git status

A merge conflict can be resolved by manual editing followed by git add [conflicted file]… and git commit -m “commit_message”