Running the simple pipeline

Set Up

Before we start attempting to process the RNA-seq data, we need to download this repository and install the relevant tools. You can get this repository by installing Git and cloning this repository from the command line, using the following code:

git clone https://github.com/ImperialCollegeLondon/ReCoDE_rnaseq_pipeline.git

The packages we need are listed in the file environment.yml. The easiest way to get them is to install conda, then run the following code from the command line:

conda env create -f environment.yml

conda activate recode_rnaseq

You must be in the project directory so that conda has access to the environment.yml file.

If this step takes too long to run, you could consider using mamba instead.

The dataset

For this tutorial, we will be using a freely available dataset that has been generated using samples from soybean plants. These data are available from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the identifier SRP009826, entitled "Comparing the response to chronic ozone of five agriculturally important legume species." RNA-seq was performed for soybean plants that were part of the control group (ambient O3 levels) and treatment group (elevated O3 levels). By the end of this exemplar, we will use the processed RNA-seq data to investigate the differences in gene expression between these two groups.

Note that these data were used previously in the paper "The bench scientist's guide to statistical analysis of RNA-Seq data" and a tutorial.

RNA-seq data can be quite large. Each sample might generate a few gigabytes of data. So, if you perform an experiment with hundreds of samples, your dataset might be in the order of terabytes! If you wish to try and process the full RNA-seq data, you can use the script data/get_data.sh to download the full data. However, these data may be too large to run on your laptop! For this reason, we have taken a subset of the full soybean data, which is included in this repository. These data are available in the data/test/ directory. For this notebook, we suggest using the test dataset to understand and run the simple RNA-seq pipeline. When we start using the more advanced pipelines (described in docs/parallelised_pipeline.md and docs/nextflow_pipeline.md) you could try applying the pipeline to the full dataset using the computing cluster.

The data generated by our RNA sequencing experiment is stored in the .fastq format. You can find these in the test/fastq/ directory. There is one file per sample, and each of the determined RNA sequences are stored in these files. The wikipedia article for the .fastq format includes the following example for a single sequence:

@SEQ_ID

GATTTGGGGTTCAAAGCAGTATCGATCAAATAGTAAATCCATTTGTTCAACTCACAGTTT

+

!''*((((***+))%%%++)(%%%%).1***-+*''))**55CCF>>>>>>CCCCCCC65

Each sequence stored in the file is described by four lines:

- A sequence identifier. This might include information on the type of sequencing being performed and the location of the RNA within the sequencer.

- The base sequence of the RNA.

- A

+character. - A quality score. There is one character for each base in line

2.. This represents the certainty of the sequencer that the base has been determined correctly.

But, you might have noticed there is another directory in data/test/. There are two files in data/test/genome/. These files were not generated in our soybean experiment. These files actually describe the soybean genome sequence and will be useful for understanding where the RNA sequences in our experiment originated from. The two files are as follows:

-

The

.fnafile (also known as a fasta) has similarities to the.fastqfiles. However, the genome sequence was determined in a previous experiment using genome sequencing, whereas the.fastqfiles using RNA sequencing to determine the RNA sequences. The.fnafile contains the genome sequences, but in this case there are no quality scores. There are only two lines for each sequence; the first line gives a unique identifier while the second represents the nucleotide sequence. Each sequence in the.fnafile represents one of the soybean chromosomes. -

The

.gtffile (also known as gene transfer format) is a tab-delimited text file that contains the genome annotation. This file tells us where each gene is located within the soybean genome. This is useful, because we can use the.fnafile to match the RNA sequences to the soybean genome, then we can lookup which gene this corresponds to using the.gtfannotation file.

Individual data processing steps

We now have some data we would like to analyse, but we need to work out how to process it. Our end goal is to count the number of RNA sequences in our samples that map to each gene in the soybean genome. Below, we will give a brief description of the analysis steps. In each step, we will use an open source tool available from conda to perform the processing. The focus on this exemplar is to show you how to create a pipeline, rather than give an in-depth explanation of the individual analysis steps; so, we suggest you look at the documentation for each tool if you are interested in how they work.

For each analysis stage, we have included a bash script that runs the relevant tool in the bin/ directory. We could call the tools directly from the command line. The primary reason we put each tool into its own bash script is so that we can use this as a framework for the pipeline. So, each of the three pipeline versions we will describe in this exemplar will all use the same scripts in bin/ to run the analysis steps. Having each analysis stage packaged neatly into their own scripts will allow us to focus on the best way to orchestrate the analysis, rather than worrying about the specifics of each tool. It should also be helpful when trying to understand how each of the three pipelines are different.

Quality control

When describing the .fastq file format, we mentioned that the sequencer produces a quality score for each base of the RNA sequence. Low quality scores indicate that the sequencer is uncertain whether the determined bases are correct. Low quality data could cause issues for our processing and analysis steps, but we can't check the quality of each sequence individually. So, the first step in our pipeline is to use the fastqc tool to generate a summary document assessing each .fastq file. The script bin/fastqc.sh runs the fastqc command line tool for a single .fastq file. So, we will have to run this script once for each of the six samples in data/test/fastq/.

Each of the bash scripts in bin/ follow a common format. The first line contains the bash "shebang" #!/bin/bash which indicates that this is a bash script. This is followed by a set of comments (lines that start with the # symbol) that explain the purpose of the script, and the inputs the script takes. The bin/fastqc.sh script takes three inputs, including the input file to be analysed and where we want to write the results to. In order to pass these inputs to the bash script we can run it from the command line as so:

bin/fastqc.sh "a" "b" "c"

The string "a" will be accessible within the script through the variable $1, "b" will be accessible through the variable $2, and so on. We can run the script multiple times, and each time we can change the arguments to the script so it runs for each of our input samples. "c" represents a directory that fastqc can save temporary files to.

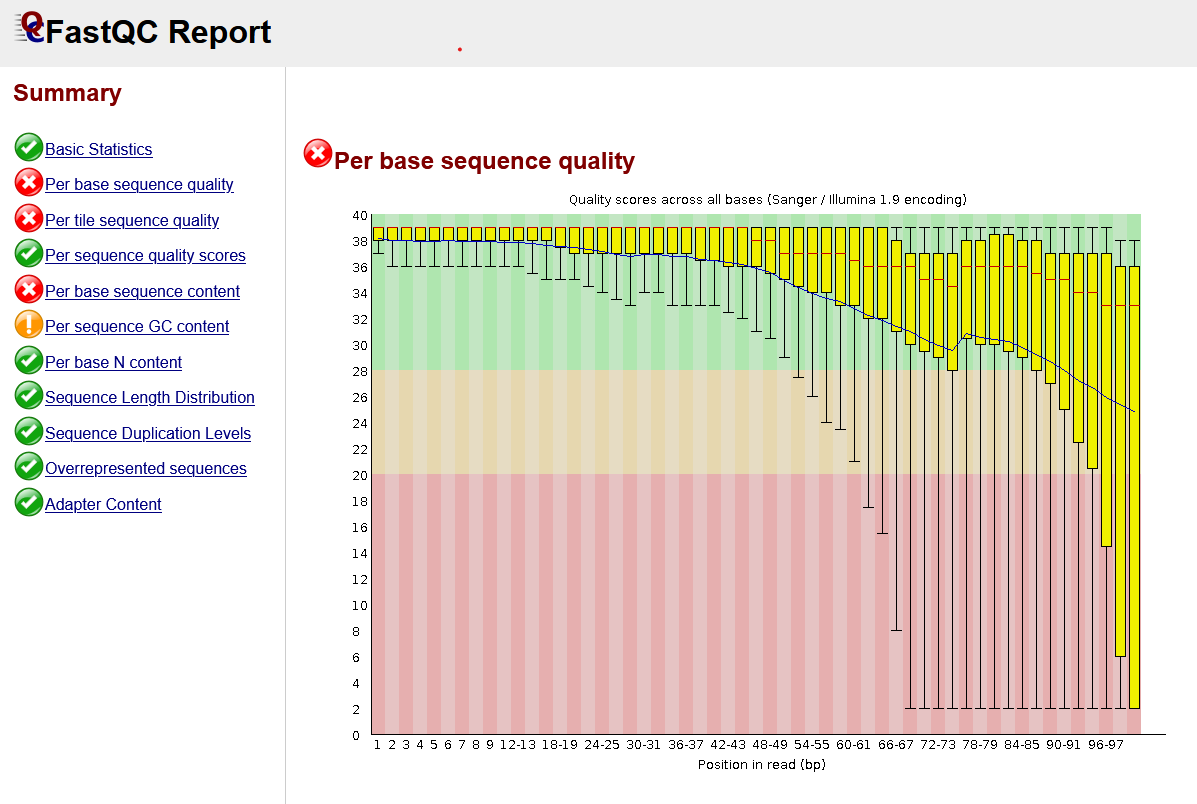

If we were to run FastQC for one of the soybean samples, the program would generate a convenient .html report for us that creates plots describing various quality control metrics. A screenshot of one of the reports is shown below. The summary on the left lists each of the quality control metrics and uses a traffic light system to indicate issues. Not all of the metrics are relevant for our analysis; if you want to understand each metric, there is documentation available online for the FastQC program that explains them.

The first metric shows a set of boxplots indicating the quality score. We mentioned these scores previously; they are available for each base in the .fastq file. FastQC converts the letter (phred) scores to numbers, where higher numbers indicate higher quality. You can see in the diagram that the quality is consistently high for each of the sequences in this .fastq file for the first ~50 bases. After this point, the quality drops off for many of the sequences. This might indicate that there are poor quality sequences that we should remove before performing further data processing steps.

Sequence trimming

In the FastQC report, we saw that the quality of some of the RNA sequences drops off after ~50 bases. For this reason, we might consider removing the low quality sections of the sequences. Tools such as Trim Galore can do this by trimming the low quality sequences. The FastQC report also included a section on "Adapter Content". As part of the sequencing process, small sequences called adapters are attached to the RNA molecules. Sometimes, these sequences are sequenced by the sequence in addition to the RNA gathered from the sample. While in this case it didn't detect any, FastQC looks for common adapter sequences that are present in the RNA sequences. In this case, trimming tools can also remove the adapter sequences before we move on to further processing steps.

The trimming step is performed by the bin/trim.sh script. Notice we pass the argument --fastqc to Trim Galore. This means that, after performing trimming, the program will run FastQC on the trimmed .fastq files so that we can verify that trimming has improved the quality distribution of the sequences.

Alignment

In the alignment stage, we will attempt to use the alignment tool STAR to match each RNA sequence to its position in the soybean genome. Alignment is quite computationally intensive, but tools like STAR have been developed that are very efficient at the task. Part of the reason STAR is so efficient is that it performs an indexing step before starting to align sequences. This is analogous to the index at the back of a book: STAR creates an index that allows it to more efficiently find sequences in a genome. So, we first have to run the script bin/star_index.sh, which calls STAR in genomeGenerate mode. We let STAR build an index for the soybean genome to ensure that the alignment stage is a lot faster. Importantly, the indexing stage only needs to be done once, while the alignment stage must be performed for each sample. The index can be then be re-used as many times as is necessary.

Having generated an index, we can run the alignment stage, using the bin/align.sh script. STAR saves the details of the alignment as a BAM (binary alignment map) file. This format is common to many different aligners and can be manipulated by lots of different bioinformatics tools. In the next stage, we will use this alignment file to count how many RNA sequences map to each gene.

You might notice that in the bin/align.sh script we also use the command line application samtools to index the BAM file that was generated by STAR. This reformats the BAM file so that it is compatible with the htseq-count tool we will apply in the next stage.

Counting

The final stage of the data processing pipeline is to count how many RNA sequences map to each gene. In this exemplar, we use the program htseq-count to do this step, but there are lots of tools that can do this. We run this tool using the bin/count.sh script, using the BAM file as input. The output of this tool is a .counts file; each line in this file contains a gene ID, followed by a tab separator, followed by the number of RNA sequences that mapped to the gene. This file is used as the first step in the downstream analysis notebook (downstream_analysis.md). In this notebook, we combine the .counts file for each sample into a single matrix, which has genes as rows and samples as columns. From here, we can apply data normalisation and begin comparing our samples.

Putting the steps together

Having briefly discussed each stage of the pipeline, we can begin to put the stages together. We could run each stage by hand from the command line, but this would become time-consuming if we had many samples and it would be difficult to record the steps we took. Instead, we will put together a script (workflows/simple_local_pipeline.sh) and run our entire analysis using a single command. The following section describes each stage of the workflows/simple_local_pipeline.sh script, before showing you how to run it from the command line.

conda activate recode_rnaseq

So, we now have access to the tools we need to perform the analysis.

We then create the DATA_DIR variable below. This is where the data we want to process is stored. The script expects to find .fastq files in the folder ${DATA_DIR}/fastq and the genome files (.gtf and .fna) in ${DATA_DIR}/genome.

DATA_DIR="data/test"

We have used the test data stored within the GitHub repository to try this pipeline out. If we wanted, we could download the full dataset using the data/get_data.sh script and change DATA_DIR to "data/". Feel free to try this out after running the pipeline on the test dataset, but the data might be too large to run on your laptop or home computer! This is fine, because we will process the full dataset on the cluster in the next notebook.

The file data/files.txt lists the sample identifiers for the data we are using in this exemplar. The script loads the names of these samples into a bash array using the following code:

while IFS=\= read srr; do

SAMPLE_SRR+=($srr)

done < data/files.txt

Next, like we did for DATA_DIR, we define RES_DIR, which indicates the folder where the results will be saved to.

Some of the pipeline steps, like STAR, can use multiple processers to speed up the analysis. To make use of this, we can set the variable NUM_CORES to a number greater than 1.

Next, we use a bash if statement, defined below. If the results folder at RES_DIR does not exist, this code creates a folder to store the results in.

if [ -e "${RES_DIR}" ]; then

echo "Results folder already exists, previous files may be overwritten."

else

mkdir "${RES_DIR}"

fi

We then create a function called create_folder, defined below. We can call the function with a single argument, as so: create_folder(my_folder). If the folder doesn't already exist, the function will create the folder.

create_folder () {

if [ ! -e "${RES_DIR}/$1" ]; then

mkdir "${RES_DIR}/$1"

fi

}

Next, we use a bash loop to run the bin/fastqc.sh step for each of our samples. In the code below, we run the fastqc script for each of the sample names in the vector SAMPLE_SRR. So, for each iteration of the loop, we give a different input .fastq file to the fastqc script, and specify a different results directory, using the variable s. After this stage, there will be a report saved to the folder 1_simple_local_pipeline_results/a_fastqc/ for each of our samples.

for s in "${SAMPLE_SRR[@]}"; do

# run fastqc on raw fastq

bin/fastqc.sh \

"${RES_DIR}/a_fastqc" \

"${DATA_DIR}/fastq/${s}.fastq.gz" \

"${RES_DIR}/a_fastqc/${s}"

done

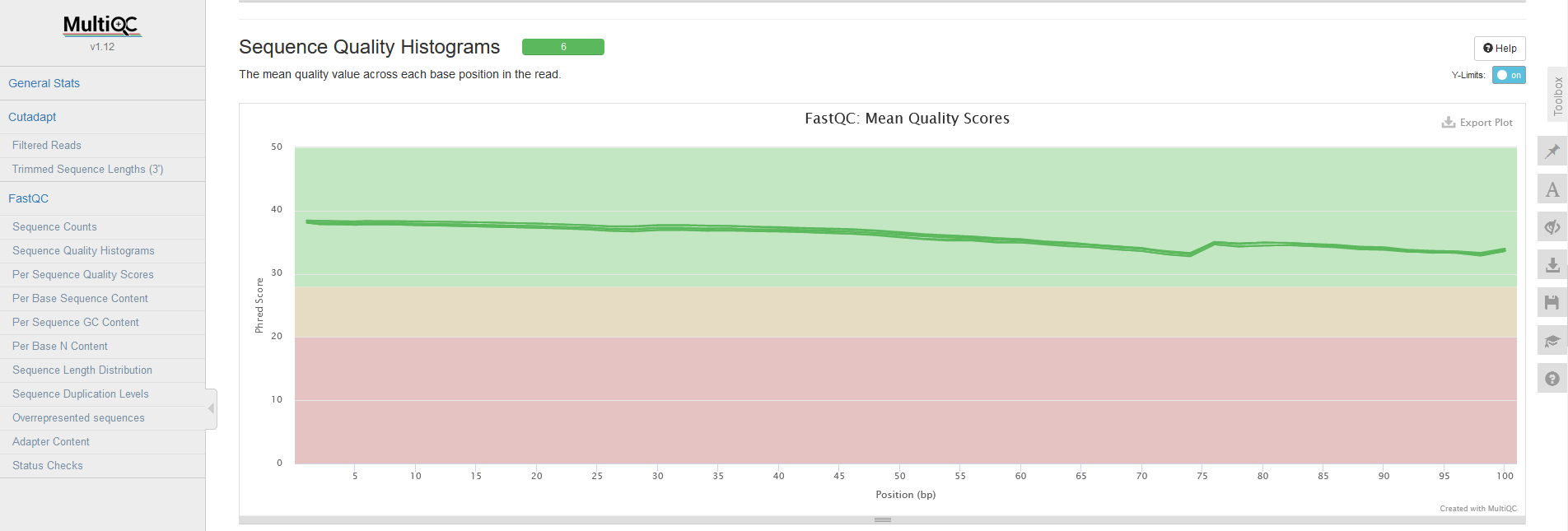

After creating these reports, we use a tool we haven't discussed yet: MultiQC. MultiQC can detect reports generated by common bioinformatics tools and cleverly combines them into a single report. So, we use the bin/multiqc.sh script to generate a single report from the six FastQC reports we generated in the previous stage. When we discussed the FastQC report we focussed on the sequence quality section. In the MultiQC report, there is a section that simultaneously visualises the average sequence quality for each sample in a single plot, which should look like the plot below. Again, we can see that the average quality score begins to drop after ~50bp.

The next step in the pipeline is to perform trimming. The code for this is similar to how we ran the FastQC tool. We loop through each of the samples, but this time we call bin/trim.sh. After we have performed trimming for each sample, we again run MultiQC to collect the reports after trimming. As you can see below, the average sequence quality is a lot better after trimming! Now we are more confident in the quality of our data, we can continue processing it.

In the next stage of the pipeline, we run the STAR indexing script. We don't do this in a loop, because we only need to generate the index once! After the index has been created, we move on to both align the sequences for each sample and perform the counting stage.

The code below again loops through each of the sample names, storing the sample name in the variable s for each iteration. Within the loop we do the following:

-

Perform alignment using STAR for a single sample at a time.

-

Remove the uncompressed

.fastqfile generated by the alignment script as it is no longer needed. -

Generate a

.countsfile using htseq-count for the sample. -

Check that the

.countsfile was successfully created. If not, something has gone wrong with the pipeline! We use a bash if statement to check the file is present in the results folder. If it is not, we use the commanderrto return an error.

for s in "${SAMPLE_SRR[@]}"; do

# perform alignment using STAR, providing the directory of the indexed genome

bin/align.sh \

"${RES_DIR}/e_star_index" \

"${RES_DIR}/c_trim/${s}_trimmed.fq.gz" \

"${RES_DIR}/f_align/${s}" \

"${NUM_CORES}"

# remove unzipped fastq

rm "${RES_DIR}/f_align/${s}.fastq"

bin/count.sh \

"${RES_DIR}/f_align/${s}Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bam" \

"${RES_DIR}/e_star_index/GCF_000004515.6_Glycine_max_v4.0_genomic.gtf" \

"${RES_DIR}/g_count/${s}"

# check the counts have been successfully created

if [ -e "${RES_DIR}/g_count/${s}.counts" ]; then

echo "Counts file for sample ${s} was successfully created"

else

err "Counts file for sample ${s} was not created"

fi

done

In the final stage of the pipeline we run MultiQC yet again. MultiQC can also assess the output of STAR and htseq-count to check that the alignment and counting stages have performed adequately. If you run the pipeline on the test dataset and check the output for STAR, you might notice that only a small proportion of the reads were actually mapped to the genome. Usually this would be a big problem! However, in this case the alignment is only poor because of the way in which the test dataset was generated. When we run the pipeline for the full soybean data, we will find that the vast majority of RNA sequences are uniquely mapped to the soybean genome.

Now we have discussed how the pipeline was created, we can actually run it. If you paste the following code into the command line, the pipeline should run for the test dataset:

workflows/simple_local_pipeline.sh

If you have any problems running the pipeline, feel free to report them as an issue on GitHub. If you find any mistakes and know how to correct them, you could also make the modification and create a pull request. If you get an error indicating any of the scripts in the project are not executable, you can fix this with the chmod command line application.

This has been a very rapid introduction to RNA-seq and its analysis, so it's normal to feel overwhelmed if this was your first exposure to the technology. After you've run the pipeline, we suggest you spend some time looking at the results of each stage and exploring the reports collected by MultiQC. There are lots of resources for learning about RNA-seq in more detail and the MultiQC report contains links to resources that explain each of the tools. However, do note that the report you generate is based on the test data and so may not be representative of a "true" RNA-seq dataset! If you want to explore the report generated for the full data, you can move on to the next notebook (docs/parallelised_pipeline.md) where we will run the pipeline for the full dataset. Alternatively, you can open the report in assets/multiqc_report.html, which contains a MultiQC report generated for the full dataset.

Limitations

In the next notebook (docs/parallelised_pipeline.md) we will move the pipeline onto the computing cluster at Imperial. This pipeline will use the same basic steps as the one described in the current document, but it will improve upon it in a few areas.

The pipeline we just ran is only set up to run on a locally on a single computer. In all likelihood, your laptop or work computer has a up to 8 cores and 16GB RAM (memory). Using tools like STAR for the human genome requires at least 30GB of memory to perform the indexing step efficiently. Furthermore, ~8 cores isn't very many if we want to start running multiple samples at the same time. Currently, the pipeline is set up to apply the tools one sample at a time using for loops. While this may be fine for a small dataset that contains only six samples, this may become a problem for larger datasets! Ideally, we would like to run many samples simultaneously so that we can process our RNA-seq data in a reasonable time-frame.

The parallelised pipeline will attempt to solve these problems. Using a computing cluster, such as Imperial's high performance computing cluster, will give you access to a huge number of processing cores and memory. We can run up to 50 different "jobs" on the computing cluster at Imperial, and each of these can have access to more cores and memory than your work computer.

There are other limitations of our current pipeline that you should be aware of, but these won't necessarily be solved by the next pipeline iteration. In the current pipeline, if a single pipeline step fails the entire pipeline fails. If the pipeline has run for 30 hours and fails on sample 100, we must fix the issue and start again from scratch!

Another problem is that we don't rigorously check that our pipeline is doing the right thing. For instance, if trimming fails for one of our samples and doesn't produce an output, the pipeline may keep going on without it. We might end up collecting our final .counts files at the end of the pipeline without ever realising we have lost a sample! We could put more work into this pipeline to make sure cases like these don't happen. For instance, we check at the end of the pipeline that all of the .counts files are accounted for. But, covering all of the possible errors is difficult and it would be easy to miss something. After covering the migration of the pipeline onto the computing cluster, we will discuss the use of a tool called Nextflow, which makes creating robust pipelines a lot simpler!