Rewriting history with Git

Last updated on 2026-02-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can multiple collaborators work efficiently on the same code?

- When should I use rebasing, merging and stashing?

- How can I reset or revert changes without upsetting my collaborators?

Objectives

- Understand the options for rewriting git history

- Know how to use them effectively when working with collaborators

- Understand the risks associated with rewriting history

Rewriting history with Git

While version control is useful to keep track of changes made to a piece of work over time, it also lets you modify the timeline of commits. There are several totally legitimate reasons why you might want to do that, from keeping the commit history clean of unsuccessful attempts to do something to incorporate work done by someone else.

There are a number of reasons why you may need to change your commit history, for example:

- You have already made a commit, but realise there are other changes you forgot to include

- You made a commit, but then changed your mind and want to remove this change from your history

- You want to “move” one or more commits so they are based on top of

some other work (e.g. new changes made to the

mainbranch)

This episode explores some of the commands git offers to

manipulate the commit history for your benefit and that of your

collaborators. But, first, we will look at another useful command.

Set aside your work safely with stash

It is not rare that, while you are working on some feature, you need to check something else in another branch. Very often this is the case when you want to try some contributor’s code as part of a pull request review process (see next episodes). You can commit the work you are doing, but if it is not in a state ready to be committed, what would you do? Or what if you start working on a branch only to realise that it is not the one that you were planning to work on?

git stash is the answer. It lets you put your current,

uncommitted work aside in a special state, turning the working directory

back to the way it was in the last commit. Then, you can easily switch

branches, pull new ones or do whatever you want. Once you are ready to

go back to work, you can recover the stashed work and continue as if

nothing had happened.

The following are the git stash commands needed to make

this happen:

-

Stash the current state of the repository, giving some message to remind yourself what this was about. The working directory becomes identical to the last commit.

-

List the stashes available in reverse chronological order (last one stashed goes on top).

-

Extract the last stash of the list, updating the working directory with its content.

-

Extract the stash with the given number from the list, updating the working directory with its content.

-

Apply the last stash without removing it from the list, so you can apply it to other branches, if needed.

-

Apply the given stash without removing it from the list, so you can apply it to other branches, if needed.

If you want more information, you can read this article on Git stash.

Practice stashing

Now try using git stash with the recipe repository. For

example:

- Add some ingredients then stash the changes (do not stage or commit them)

- Modify the instructions and also stash those change

Then have a look at the list of stashes and bring those changes back

to the working directory using git stash pop and

git stash apply, and see how the list of stashes changes in

either case.

Amend

This is the simplest method of rewriting history: it lets you amend the last commit you made, maybe adding some files you forgot to stage or fixing a typo in the commit message.

After you have made those last minute changes – and

staged them, if needed – all you need to do to amend the

last commit while keeping the same commit message is:

Or this:

if you want to write a new commit message.

Note that this will replace the previous commit with a new one – the commit hash will be different – so this approach must not be used if the commit was already pushed to the remote repository and shared with collaborators.

Edit commit message with your editor

If you run git commit without either the

--no-edit or -m flags, it will open a text

editor to allow you to enter a commit message. If you are using the

--amend flag, the text editor will contain the commit

message for the commit you are amending.

You can edit the commit message in your text editor however you like, then, when you have finished, save and exit. For longer commit messages, the convention is to provide a short, one-line summary on the first line, followed by an empty line, then by a more detailed description.

Challenge

For details on how to choose which text editor Git will use, see the setup instructions.

Reset

The next level of complexity rewriting history is reset:

it lets you redo the last (or last few) commit(s) you made so you can

incorporate more changes, fix an error you have spotted and that is

worth incorporating as part of that commit and not as a separate one or

just improve your commit message. Unlike git revert,

git reset will retrospectively alter your commit history,

so it should not be used when you have already shared

work with collaborators.

This resets the staging area to match the most recent commit, but

leaves the working directory unchanged – so no information is lost. Now

you can review the files you modified, make more changes or whatever you

like. When you are ready, you stage and commit your files, as usual. You

can go back 2 commits, 3, etc with HEAD^2,

HEAD^3… but the further you go, the more chances there are

to leave commits without a parent commit. Resulting in a messy (but

potentially recoverable) repository, as information is not lost. You can

read about this recovery process in this blog

post in Medium.

A way more dangerous option uses the flag --hard. When

doing this, you completely remove the commits up to the specified one,

updating the files in the working directory accordingly. In other words,

any work done since the chosen commit will be completely

erased.

To undo just the last commit, you can do:

Otherwise, to go back in time to a specific commit, you would do:

reset vs revert

git revert was discussed

in the introductory course.

reset and revert both let you undo things

done in the past, but they both have very different use cases.

-

resetuses brute force, potentially with destructive consequences, to make those changes and is suitable only if the work has not been shared with others already. Use it when you want to get rid of recent work you’re not happy with and start all over again. -

revertis more lightweight and surgical, to target specific changes and creating new commits to history. Use it when code has already been shared with others or when changes are small and clearly isolated.

Don’t mess with the salt

Let’s put this into practice! After all the work done in the previous episode adjusting the amount of salt, you conclude that it was nonsense and you should keep the original amount. You could obviously just create a new commit with the correct amount of salt, but that will leave your poor attempts to improve the recipe in the commit history, so you decide to totally erase them.

First, we check how far back we need to go with

git graph:

OUTPUT

* c9d9bfe (HEAD -> main) Merged experiment into main

|\

| * 84a371d (experiment) Added salt to balance coriander

* | 54467fa Reduce salt

* | fe0d257 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\|

| * 99b2352 Reduced the amount of coriander

* | 2c2d0e2 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\|

| * d9043d2 Try with some coriander

* | 6a2a76f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* 57d4505 (origin/main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 5cb4883 Added 1/2 onion

* 43536f3 Added instruction to enjoy

* 745fb8b Adding ingredients and instructionsWe can see in the example that we want to discard the last three

commits from history and go back to fe0d257, when we merged

the experiment branch after reducing the amount of

coriander. Let’s do it (use your own commit hash!):

Now, the commit history should look like this:

OUTPUT

* 84a371d (experiment) Added salt to balance coriander

| * fe0d257 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'experiment'

| |\

| |/

|/|

* | 99b2352 Reduced the amount of coriander

| * 2c2d0e2 Merge branch 'experiment'

| |\

| |/

|/|

* | d9043d2 Try with some coriander

| * 6a2a76f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* 57d4505 (origin/main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 5cb4883 Added 1/2 onion

* 43536f3 Added instruction to enjoy

* 745fb8b Adding ingredients and instructionsNote that while the experiment branch still mentions the

adjustment of salt, that is no longer part of the main

commit history. Your working directory has become identical to that

before starting the salty adventure.

Changing History Can Have Unexpected Consequences

Like with git commit --amend, using

git reset to remove a commit is a bad idea if you have

already shared it with other people. If you make a

commit and share it on GitHub or with a colleague by other means then

removing that commit from your Git history will cause inconsistencies

that may be difficult to resolve later. We only recommend this approach

for commits that are only in your local working copy of a

repository.

Removing branches once you are done with them is good practice

Over time, you will accumulate lots of branches to implement

different features in your code. It is good practice to remove them once

they have fulfilled their purpose. You can do that using the

-D flag with the git branch command:

Getting rid of the experiment

As we are done with the experiment branch, let’s delete

it to have a cleaner history.

Now, the commit history should look like this:

OUTPUT

* fe0d257 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 99b2352 Reduced the amount of coriander

* | 2c2d0e2 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\|

| * d9043d2 Try with some coriander

* | 6a2a76f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* 57d4505 (origin/main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 5cb4883 Added 1/2 onion

* 43536f3 Added instruction to enjoy

* 745fb8b Adding ingredients and instructionsNow there is truly no trace of your attempts to change the content of salt!

Incorporate past commits with rebase

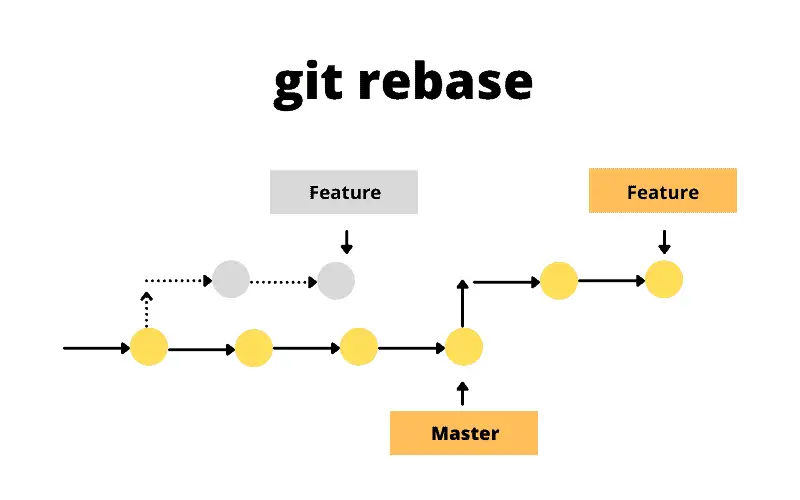

Rebasing is the process of moving or combining a sequence of commits to a new base commit. In other words, you take a collection of commits that you have created that branched off a particular commit and make them appear as if they branched off a different one.

The most common use case for git rebase happens when you

are working on your feature branch (let’s say experiment)

and, in the meantime there have been commits done to the base branch

(for example, main). You might want to use in your own work

some upstream changes done by someone else or simply keep the history of

the repository linear, facilitating merging back in the future.

The command is straightforward:

where NEW_BASE can be either a commit hash or a branch

name we want to use as the new base.

The following figure illustrates the process where, after rebasing, the two commits of the feature branch have been recreated after the last commit of the main branch.

For a very thorough description about how this process works, read this article on Git rebase.

Practice rebasing

We are going to practice rebasing in a simple scenario with the recipe repository. We need to do some preparatory work first:

- Create a

spicybranch - Add some chillies to the list of ingredients and commit the changes

- Switch back to the

mainbranch - Add a final step in the instructions indicating that this should be served cold

- Go back to the

spicybranch

If you were to add now instructions to chop the chillies finely and

put some on top of the mix, chances are that you will have conflicts

later on when merging back to main. We can merge main into

spicy, as we did in the previous episode, but that will

result in a non-linear history (not a big deal in this case, but things

can get really complicated).

So let’s use git rebase to bring the spicy

branch as it it would have been branched off main after

indicating that the guacamole needs to be served cold.

After the following commands (and modifications to the files) the repository history should look like the graph below:

BASH

git switch -c spicy

# add the chillies to ingredients.md

git stage ingredients.md

git commit -m "Chillies added to the mix"

git switch main

# Indicate that should be served cold in instructions.md

git stage instructions.md

git commit -m "Guacamole must be served cold"

git graphOUTPUT

* d10e1e9 (HEAD -> main) Guacamole must be served cold

| * e0350e4 (spicy) Chillies added to the mix

|/

* 5344d8f Revert "Added 1/2 onion"

* fe0d257 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 99b2352 Reduced the amount of coriander

* | 2c2d0e2 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\|

| * d9043d2 Try with some coriander

* | 6a2a76f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* 57d4505 (origin/main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 5cb4883 Added 1/2 onion

* 43536f3 Added instruction to enjoy

* 745fb8b Adding ingredients and instructionsNow, let’s go back to spicy and do the

git rebase:

OUTPUT

* a34042b (HEAD -> spicy) Chillies added to the mix

* d10e1e9 (main) Guacamole must be served cold

* 5344d8f Revert "Added 1/2 onion"

* fe0d257 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\

| * 99b2352 Reduced the amount of coriander

* | 2c2d0e2 Merge branch 'experiment'

|\|

| * d9043d2 Try with some coriander

* | 6a2a76f Corrected typo in ingredients.md

|/

* 57d4505 (origin/main) Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

* 5cb4883 Added 1/2 onion

* 43536f3 Added instruction to enjoy

* 745fb8b Adding ingredients and instructionsCan you spot the difference with the coriander experiment? Now the commit history is linear and we have avoided the risk of conflicts.

- There are several ways of rewriting git history, each with specific use cases associated to them

- Rewriting history can have unexpected consequences and you risk losing information permanently

- Reset: You have made a mistake and want to keep the commit history tidy for the benefit of collaborators

- Stash: You want to do something else – e.g. switch to someone else’s branch – without losing your current work

- Rebase: Someone else has updated the main branch while you’ve been working and need to bring those changes to your branch

- More information: Merging vs. Rebasing