Visualizing data with Matplotlib

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I plot my data?

How can I save my plot for publishing?

Objectives

Plot simple graphs from data.

Visualizing data

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and

the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire

lecture of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While

there is no official plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto standard. First, we will

import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a

heat map of our data:

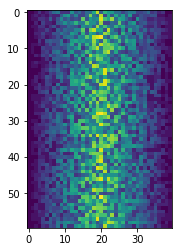

import matplotlib.pyplot

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

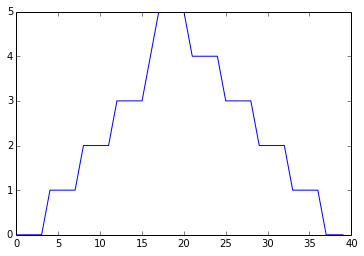

Blue pixels in this heat map represent low values, while yellow pixels represent high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period.

Some IPython Magic

If you’re using an IPython / Jupyter notebook, you’ll need to execute the following command in order for your matplotlib images to appear in the notebook when

show()is called:%matplotlib inlineThe

%indicates an IPython magic function - a function that is only valid within the notebook environment. Note that you only have to execute this function once per notebook.

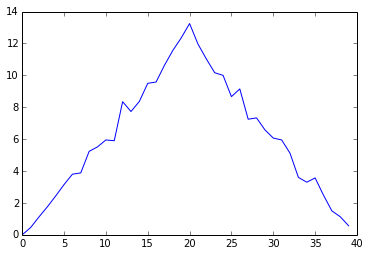

Let’s take a look at the average inflammation over time:

ave_inflammation = numpy.mean(data, axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Here, we have put the average per day across all patients in the variable ave_inflammation, then

asked matplotlib.pyplot to create and display a line graph of those values. The result is a

roughly linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: we might instead expect a sharper rise and slower

fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

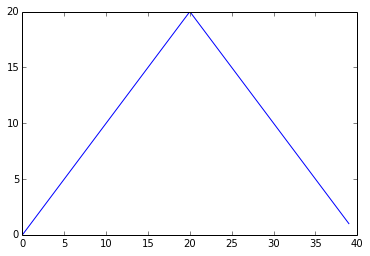

max_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

min_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

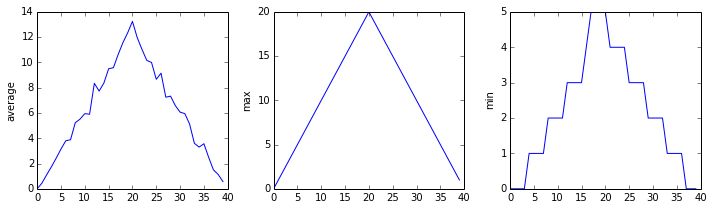

The maximum value rises and falls smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither trend seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data. This insight would have been difficult to reach by examining the numbers themselves without visualization tools.

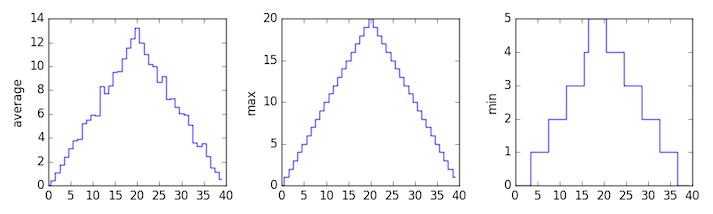

Grouping plots

You can group similar plots in a single figure using subplots.

This script below uses a number of new commands. The function matplotlib.pyplot.figure()

creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize

tells Python how big to make this space. Each subplot is placed into the figure using

its add_subplot method. The add_subplot method takes 3

parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter

refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameter denotes which subplot

your variable is referencing (left-to-right, top-to-bottom). Each subplot is stored in a

different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3). Once a subplot is created, the axes can

be titled using the set_xlabel() command (or set_ylabel()).

Here are our three plots side by side:

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The call to loadtxt reads our data,

and the rest of the program tells the plotting library

how large we want the figure to be,

that we’re creating three subplots,

what to draw for each one,

and that we want a tight layout.

(If we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(),

the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

Scientists Dislike Typing

We will always use the syntax

import numpyto import NumPy. However, in order to save typing, it is often suggested to make a shortcut like so:import numpy as np. If you ever see Python code online using a NumPy function withnp(for example,np.loadtxt(...)), it’s because they’ve used this shortcut. When working with other people, it is important to agree on a convention of how common libraries are imported.

Plot Scaling

Why do all of our plots stop just short of the upper end of our graph?

Solution

Because matplotlib normally sets x and y axes limits to the min and max of our data (depending on data range)

If we want to change this, we can use the

set_ylim(min, max)method of each ‘axes’, for example:axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Update your plotting code to automatically set a more appropriate scale. (Hint: you can make use of the

maxandminmethods to help.)Solution

# One method axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylim(0,6)Solution

# A more automated approach min_data = numpy.min(data, axis=0) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(min_data) axes3.set_ylim(numpy.min(min_data), numpy.max(min_data) * 1.1)

Drawing Straight Lines

In the center and right subplots above, we expect all lines to look like step functions because non-integer value are not realistic for the minimum and maximum values. However, you can see that the lines are not always vertical or horizontal, and in particular the step function in the subplot on the right looks slanted. Why is this?

Solution

Because matplotlib interpolates (draws a straight line) between the points. One way to do avoid this is to use the Matplotlib

drawstyleoption:import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0)) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid') fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Make Your Own Plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation (

numpy.std) of the inflammation data for each day across all patients.Solution

std_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.std(data, axis=0)) matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Moving Plots Around

Modify the program to display the three plots on top of one another instead of side by side.

Solution

import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',') # change figsize (swap width and height) fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(3.0, 10.0)) # change add_subplot (swap first two parameters) axes1 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 1) axes2 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 2) axes3 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 3) axes1.set_ylabel('average') axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0)) axes2.set_ylabel('max') axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) fig.tight_layout() matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Key Points

Use the

pyplotlibrary frommatplotlibfor creating simple visualizations.Many styles of plot are available: see the Python Graph Gallery for more options.