Committing and History

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How do I start a project using Git?

How do I record changes made in a project?

How do I view the history of a project?

How can I correct mistakes I make with Git?

Objectives

Explain how and why Git must be configured

Explain what a repository is

List the commands used to create a Git commit

Describe the difference between the working directory, staging area and index

Use a commit history to find information about a repository

List the commands that can be used to undo previous commits

Explain potential issues with rewriting the commit history

First Things First

You should have already completed the setup instructions for this workshop and have Git installed. Launch a command line environment (on Windows launch “Git Bash” from the Start menu; on Linux or macOS start a new Terminal). We will use this command line interface throughout these materials. We focus on teaching Git with the command line as we believe this is the most thorough and portable way to communicate the underlying concepts.

You can use the command line to interact with Git but there is still some extra information you must provide before it is ready to use. Enter the following commands, using your relevant personal information as required.

git config --global user.name "FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME"

git config --global user.email "email@example.com"

The information provided here will be included with every snapshot you record

with Git. In collaborative projects this is used to distinguish who has made

what changes. The --global part of the command sets this information for

any projects on which you might work on this computer. Therefore you only need

to perform the above commands once for each new computer Git is installed on.

The Command Line Interface

For users not generally familiar with using command line interfaces it’s worth taking a moment to consider the commands that were just run. To understand what we just did let’s break down the first command:

git

- This simply indicates to the command line that we want to something with Git.

- All commands that we use today will start with this.

config

- Git is a very powerful tool with lots of functionality so next we need to indicate what we want to do with it.

- Putting

configindicates we want to change something about how Git is configured.

--global

- Parts that start with dashes are called flags and are used to fine tune the behaviour of the command given.

- The role of the

--globalflag is explained above.

user.name "FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME"

- Finally we tell Git what we want to configure and the details to use.

Creating a Repository

Warning for Linux and macOS users

Before you move onto this exercise, you should run the following command:

$ git config --global core.autocrlf inputThis will stop git recording changes to line endings, which can – depending on which text editor you’re using – result in git erroneously thinking every line in a file has changed.

For a longer explanation of why this may be needed, see GitHub’s comprehensive explanation here.

Now that Git is ready to use let’s see how to start using it with a new project. In Git terminology a project is called a repository (frequently shortened to “repo”).

For this workshop you were provided with a zip file. If

you have not already done so, please download it and place it in your home

directory. The zip file contains a directory called recipe which in turn

contains 2 files - instructions.md and ingredients.md. This is the project

we’ll be working with; whilst not based on code this recipe for guacamole is an

intuitive example to illustrate the functionality of Git. To extract the archive

run the following command:

unzip recipe.zip

Then change the working directory of the terminal the newly created recipe

directory:

cd recipe

You’ll need to repeat cd recipe if you open a new command line interface. Feel

free to open ingredients.md and instructions.md and take a look at them (use

a normal file browser if you’re not comfortable doing this on the command

line). Files with a .md extension are using a format called Markdown, don’t

worry about this now, for our immediate purposes these are just text files. Use

of Markdown and GitHub will come up in the next session however.

To start using Git with our recipe we need to create a repository for it. Make

sure the current working directory for your terminal is recipe and run:

git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/username/recipe/.git/

The path you see in the output will vary depending on your operating system.

masterandmainbranchesA branch is a specific version of the state and history of the work in the repo. Traditionally, the default branch name whenever you

inita repository wasmaster. However, the awareness of the online community has improved lately and some tools, like GitHub, use nowmainas the default name instead. You can read the rationale in this link.If you are using

gitversion 2.28 or higher (you can find the version you are using withgit --version) you can change the default branch name for all new repositories with:$ git config --global init.defaultBranch mainFor existing repositories or if your git version is lower than 2.28, you can create the

masterbranch normally and then re-name it with:$ git branch -m master mainDepending on your exact version of git, you might get an error like the following when trying to rename the branch:

error:: refname refs/heads/master not found fatal: Branch rename failedIf that is your case, make sure there are not uncommitted files in the repository, and that you have made at least one commit (see below for more information about commits). Ultimately, you can simply create a separate branch called

mainand use that one as your default branch rather thanmaster, which you can then delete.We will use

mainas the default branch name throughout the workshop. Branches will be covered in detail in our intermediate Git course.

Creating The First Snapshot

Before we do anything else run the following:

git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

ingredients.md

instructions.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

This is a very useful command that we will use a lot. It should be your first port of call to figure out the current state of a repository and often suggests commands that can be used for different tasks.

Don’t worry about all the output for now, the important bit is that the two files we already have are untracked in the repository (directory). Git does not track any files automatically so we need to do this explicitly. To do this, we first add the files to Git’s staging area, like so:

git stage ingredients.md

git stage instructions.md

git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: ingredients.md

new file: instructions.md

Now this change is staged and ready to be committed (note that we could

have saved some typing here with the command git stage ingredients.md

instructions.md).

git stagevsgit addNote that you will sometimes see the

git stagecommand written asgit add(e.g. in the command output above). These commands are completely equivalent, but in this course we will usegit stagethroughout for consistency.

Let us now commit the change to the repository, with a brief but informative description of the change:

git commit -m "adding ingredients and instructions"

[main (root-commit) aa243ea] adding ingredients and instructions

2 files changed, 8 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 ingredients.md

create mode 100644 instructions.md

We have now finished creating the first snapshot in the repository. Named after the command we just used, a snapshot is usually referred to in Git as a commit, or sometimes a changeset. We will use the term “commit” from now on. Straight away query the status to get this useful command into our muscle memory:

git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree clean

The output we get now is very minimal. This highlights an important point about the status command - its purpose is to report on changes in the repository relative to the last commit. In order to see the commits made in a project we can use:

git log

commit b7cd5f6ff57968a7782ff8e74cc9921cc7463c30 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Mon Dec 30 12:51:04 2019 +0000

adding ingredients and instructions

We’ll talk in more detail about the output here but for now the main point is to recognise that a commit has been created with your personal information and the message you specified.

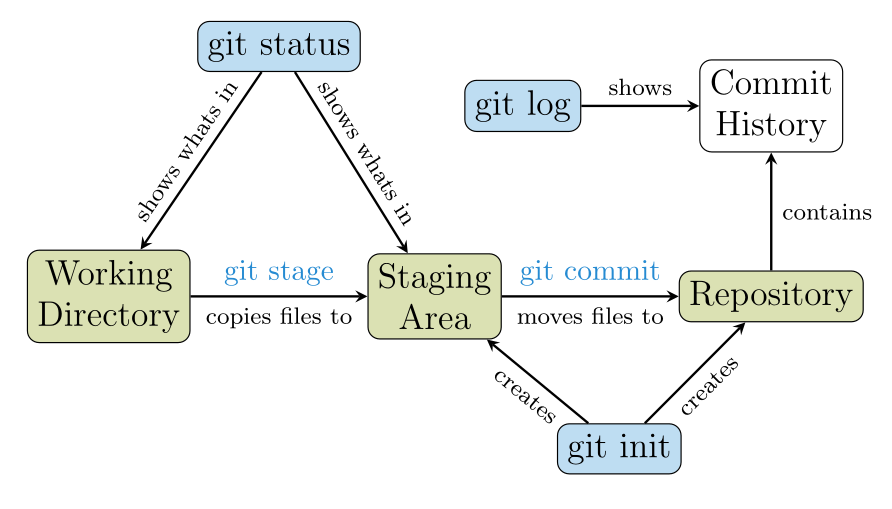

Staging and Committing

For our first commit we saw that this is a two step process - first we use git

stage then git commit. This is an important pattern used by Git. To understand

this in more detail it’s useful to know that git has three ‘areas’.

- The Working Directory (or Working Tree)

- This is the copy of the files that you actually work with in a normal way.

- The Staging Area (or index)

- When you run

git stagea copy of a file is taken from the working tree and placed here. - New (untracked) files must be added to the staging area before git will track them.

- If a tracked file has been changed it must be added to staging area for that change to be included in a commit.

- This is known as staging files or adding them to the staging area.

- Only files in the staging area are included in a commit.

- When you run

- The Repository

- When you run

git commita new commit is created in the repository. - All files in the staging area are moved to the repository as part of the new commit.

- When you run

The relationship between the commands we’ve seen so far and the different areas

of Git are show below:

Exercise: Create some more commits

Add “1/2 onion” to

ingredients.mdand also the instruction “enjoy!” toinstructions.md. Do not stage the changes yet.When you are done editing the files, try:

git diffThere’s a lot of information here so take some time to understand the output. If your output doesn’t contain colours you may want to run

git diff --color.First, practice what we have just seen by staging and committing the changes to

instructions.md. Remember to include an informative commit message.Now, run

git statusandgit diff. Then, stage and commit the changes toingredients.mdbut, after each step rungit status,git diffandgit diff --staged. What is the difference between the two diff commands? How does running staging and committing change the status of a file?

Why stage?

The last exercise highlights the reason Git uses a staging area before making commits. You can make file changes as you want all at once and then group them together logically to make individual commits. We’ll see why having only sets of related changes for a specific purpose in a single commit is so useful later on.

Git History and Log

We used git log previously to see the first commit we created. Let’s run it

again now.

git log

commit b6ff1ca61f08241ec741f6fc58ab2a443a253d89 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:32:04 2019 +0000

Added 1/2 onion to ingredients

commit 2bf7ece2f57594873678f9c17832010730970b28

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:28:19 2019 +0000

Added instruction to enjoy

commit ae3255af37e82a98c57f16a057acd1ad5a15ff28

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:27:14 2019 +0000

Adding ingredients and instructions

Your output will differ from the above not only in the date and author fields but in the alphanumeric sequence (hash) at the start of each commit.

- We can browse the development and access each state that we have committed.

- The long hashes following the word commit are random and uniquely label a state of the code.

- Hashes are used when comparing versions and going back in time.

- If the first characters of the hash are unique it is not necessary to type the entire hash.

- Output is in reverse chronological order, i.e. newest commits on top.

- Notice the label HEAD at the top, this indicates the commit that the current working directory is based on.

What is a commit hash?

A commit hash is a string that uniquely identifies a specific commit. They are the really long list of numbers and letters that you can see in the output above after the word

commit. For example,ae3255af37e82a98c57f16a057acd1ad5a15ff28for the last entry.Occasionally, you will need to refer to a specific commit using the hash. Normally, you can use just the first 5 or 6 elements of the hash (eg. for the hash above it will be enough to use

ae3255a) as it is very unlikely that there will be two commit hashes with identical starting elements.Throughout this course, we will indicate that you need to use the hash with

[commit-hash]. On those occasions, replace the whole string (including the square brackets!) with the hash id. For example, if you need to usegit show(see example below) with the above commit hash, you will run:git show ae3255a

Exercise: Recalling the changes for a commit

The command

git logshows us the metadata for a commit but to see the file changes recorded in a commit you can usegit show:git show [commit-hash]Use one of the commit hashes from your Git history. To see the contents of a particular file from when the commit was made, try:

git show [commit-hash]:ingredients.md

To Err is Human, To Revert Divine

Rewriting History

A very common and frustrating occurrence when using Git is making a commit and then realising you forgot to stage something, or staged something you shouldn’t have. Fortunately the Git commit history is not set in stone and can be changed.

To undo the most recent commit you can use:

git reset --soft HEAD^

Follow this up with:

git log

commit 2bf7ece2f57594873678f9c17832010730970b28 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:28:19 2019 +0000

Added instruction to enjoy

commit ae3255af37e82a98c57f16a057acd1ad5a15ff28

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:27:14 2019 +0000

Adding ingredients and instructions

Notice we’ve gone from three commits to two. Let’s also run:

git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: ingredients.md

This shows that the content which was part of the commit has been moved back into the staging area.

From here we can choose what to do. We could stage some additional changes and create a new commit, or we could unstage ingredients.md and do something else entirely. For now let’s just restore the commit we removed by committing again:

git commit -m "Added 1/2 onion to ingredients"

Changing History Can Have Unexpected Consequences

Using

git resetto remove a commit is only a good idea if you have not shared it yet with other people. If you make a commit and share it on GitHub or with a colleague by other means then removing that commit from your Git history will cause inconsistencies that may be difficult to resolve later. We only recommend this approach for commits that are only in your local working copy of a repository.

Reversing a Commit

Sometimes after making a commit we later (sometimes multiple commits later) realise that it was misguided and should not have been included. For instance, it’s a bit of cliché to tell people to “enjoy” at the end of a recipe, so let’s get rid of it with:

git revert --no-edit [commit-hash]

[main a70e1c5] Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

Date: Tue Dec 31 12:37:47 2019 +0000

1 file changed, 1 deletion(-)

Check the contents of instructions.md and you should see that the enjoy

instruction is gone. To fully understand what revert is doing check out the

repository history:

git log

commit ddef60e05eae3cc73ea5be3f98df6ae372e43750 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Christopher Cave-Ayland <c.cave-ayland@imperial.ac.uk>

Date: Tue Dec 31 14:55:52 2019 +0000

Revert "Added instruction to enjoy"

This reverts commit 2bf7ece2f57594873678f9c17832010730970b28.

...

Using git revert has added a new commit which reverses the changes made in the

specified commit.

This is a good example of why making separate commits for each change is a good

idea. If we had committed the changes to both ingredients.md and

instructions.md at once we would not have been able to revert just the enjoy

instruction.

The Ultimate Guide to Undoing in Git

It can be quite easy to get into a messy state in Git and it can be difficult to get help via a search engine that covers your exact situation. If you need help we recommend consulting “On undoing, fixing, or removing commits in git”. This page contains a very comprehensive and readable guide to getting out of a sticky situation with Git.

Key Points

Setup Git with your details using

git config --global user.name "FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME"andgit config --global user.email "email@example.com"A Git repository is the record of the history of a project and can be created with

git initGit records changes to files as commits

Git must be explicitly told which changes to include as part of commit (known as staging changes) with

git stage [file]...Staged changes can be stored in a commit with

git commit -m "commit message"You can check which files have been changed and/or staged with

git statusYou can see the full changes made to files with

git difffor unstaged files andgit diff --stagedThe commit history of a repository can be checked with

git logThe command

git revert commit_refcreates a new commit which undoes the changes of the specified commitThe command

git reset --soft HEAD^removes the previous commit from the history